Coming to Terms with Sound

Björn Gottstein on the music of Ernstalbrecht Stiebler

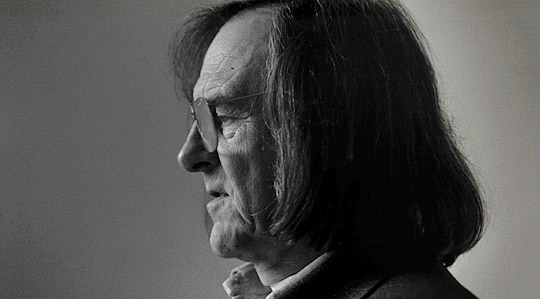

Rebelling against codes of serialism that were so dominant in the 1960s, Ernstalbrecht Stiebler contributed to a new understanding of sound through work that can also be credited as laying the foundation for modern-day minimalistic music.

In the early 20th Century, the Austrian biologist Paul Kammerer coined the concepts of "the law of the series" and the "duplicity of events". These laws can also apply to the history of music. Much has been invented several times over without a direct link ever being drawn between events, eg. the double reed, the string quartet, dodecaphony…

In the 20th Century, across decades and continents, musicians came to the realization that we would have to approach sound differently than in the past, that we must create a different sensitivity to sound in order to significantly expand the experience of music. That this was recognized by such diverse musicians and composers such as Giacinto Scelsi, Eliane Radigue, Klaus Schulze, or Bernhard Günter to name only a few, and that these musicians were mainly not aware of each other, illustrates the fact that the history of ideas of music cannot be derived from biographies of individual artists but must be seen as a social movement.

Ernstalbrecht Stiebler is yet another musician to have contributed to a new understanding of sound since the 1960s. Stiebler, born in Berlin in 1934, had studied composition in Hamburg and attended classes with Karlheinz Stockhausen in Darmstadt. Even in the 1950s, he inwardly rebelled against the codes of serial music, which determined music through series and parameters by using constant change and the non-identicalness of events, thus creating a constant state of musical unrest. In the late 50s, this uneasiness with the teachings of his mentors led to a first encounter with John Cage, who was then preaching a different music, one that is not subject to the will and taste of the composer, but unfolds in a random and disjointed manner. Stiebler, who at that time was already familiar with the teachings of Yoga, could relate to Cage's Zen Buddhist-inspired thought, even if today he admits that Cage's monastic essence appealed to him less than the freer and more informal use of sound and form pursued by Morton Feldman.

As a result of these impressions and thoughts, Stiebler composed the string trio Extensions I in 1963. With long tones, little movement, and much repetition, Stiebler took the step towards a music increasingly free of expression and gesture. By focusing only on a few notes, by repeating tones and intervals, and by choosing slow tempi, Stiebler gave sound new opportunities for development. This leads to a different sensitivity, where the listener almost inevitably enters into the internal structure of the sound. For example, if the pressure of the bow is increased on a cello string, then the sound not only gets louder, but the overtones also change. To perceive these changes takes time, however, and the composer must grant the sound that time.

Stiebler, alongside composers like Giacinto Scelsi, count among the first to have shaped the inner workings and phenomenons of sound to make them tangible. Around 1960, composed music began to include an experience of sound as can be found in trance and ritual music, and with instruments like the didgeridoo. Stiebler does not fundamentally reject spiritual connotations; meditation is a very precise exercise that requires a high level of concentration and ultimately enables another state of consciousness, and such a state is something that one can, or even should, wish to achieve from an aesthetic experience.

Through reductionism, repetition, and slowing down, other phenomena enter into the listener’s consciousness, including space. The temporal extension of the sound allows the physical (sound)wave to spread out in space, and this physical space then gives way to other spaces, which Stiebler calls “interior spaces”. In describing “interior spaces” Stiebler makes reference to the space-body concepts of Taoism, where in addition to the real body of space, there exists an aural body of space, an emotional body of space, a mental body of space, and so on. Music can not only create all of these spaces and make them tangible, but crucially also allows them to flow and merge into one another. Through his work in differentiating sonic spaces in his compositions and his exploratory work with microtones, Stiebler helped open peoples’ ears to the fact that we also can still learn to hear something between well-known intervals.

The fact that Stiebler's position has not quite been able to assert itself among other aesthetic standpoints, and that he is far from being recognized as a pioneer and visionary, has various causes. As a radio producer (1969-95 at Hessischer Rundfunk) Stiebler could not devote his full commitment to his own music, and as a concert promoter he refused to have his own works performed. Furthermore, the position the composer adopted is one of restraint; Stiebler and his music do not draw attention to themselves and they are not meant to be heard loudly. With such a discreet attitude, one wonders whether Stiebler had asked many questions before their time, and whether his body of work should be reassessed in retrospect. Indeed, questions about musical space, about the meaning of repetition, about the radical reduction of material, or the spirituality of sound, have been raised again and again in recent years, and in some cases have led to similar conclusions as Stiebler's work. Examples include the reductionist phase of Berlin’s improvised music scene Echtzeitmusik (literally translated as "real-time music"), the Japanese Onkyo movement, the auscultation of space that can be found in sound art, or the recent preoccupation with Gilles Deleuze's "Difference and Repetition" in musical discourse, among others.

At the same time, there is one mistake that must not be made, namely to ascertain fundamental similarities in musical character based on similarities found under certain circumstances in the actual sounds, the sound design, or even in the aesthetic premises of works. What Giacinto Scelsi suggested in 1959 with his "Quatro pezzi su una sola nota", what Eliane Radigue achieved in 1971 with Chry-ptus, what Klaus Schulze attempted in 1972 with his album Irrlicht – each of these are entirely distinct attempts to come to terms with sound.

It is important to understand that Stiebler’s works are not composed intuitively or off the cuff: even if a fourth is simply struck in four different octaves on the piano, there are compositional strategies at work. Repetitions and pitch shifts do not occur based on the moment, but always with a view of the whole. Micro-intervals are carefully set in advance to sixths, etc.

Even if it is a fortunate coincidence that in the 21st Century one can look back on so many similarities in such diverse musical currents, their differences are at least as significant. The question then is not so much to what extent Ernstalbrecht Stiebler and the discovery of slow tempos in the synthpop of the seventies share a common basis, but rather how they came to similar questions from such different angles. Such a question touches on the social psychology of an era, which merits a significant analysis.

A series of works by Ernstalbrecht Stiebler will be performed on Thursday January 31st at HAU2, as part of CTM.13.

Björn Gottstein is a music journalist based in Berlin. He writes about electronic music and the history of the avantgarde.

Translated from German by Alexander Paulick-Thiel.